FAMOUS WORKS:

Ninety-Five Theses

Some of those who purchased indulgences from Tetzel were Luther's parishioners. Appalled at the abuse, Luther penned 95 statements against the practice of selling indulgences. On October 31, 1517, he nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the castle church in Wittenburg, a common method of initiating scholarly discussion.

The actual title of the famous theses is Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences. Luther wrote them in Latin with an intended audience of his university colleagues, and could not have imagined the impact they would have on Christianity and on Europe.

Diet of Augsburg

But his Theses were translated into German, and using to Guttenberg's newly-invented movable-type printing press, quickly copied and disseminated all over Saxony. The Pope himself received a copy, but he was unimpressed. He is said to have inquired, "What drunken German monk wrote these?" He directed the Augustinian order to deal with the situation.

When invited to the order's next meeting, in April 1518, Luther feared for his life, and for good reason. Heresy had cost the lives of many reformers before him. But to his surprise, Luther found that many of his fellow friars agreed with him. Others simply regarded the issue as yet another dispute between the rivals Dominicans and Augustinians.

In October 1518, an imperial diet ("DEE-it") - a meeting of the Holy Roman Empire's princes and nobles - was held in Augsburg. The Pope sent a representative to the meeting with instructions to convince the German princes to support a crusade against the Turks. A secondary task was to meet with Luther and convince him to recant. Not entirely confident he would return home alive, Luther nevertheless attended the meeting in the hopes of defending his views.

Unfortunately, the papal representative Cardinal Cajetan showed no interest in debating issues, only in persuading Luther to recant. Like Jan Hus, who was burned at the stake for heresy 100 years prior, Luther responded that he would be glad to recant if shown his errors from the Scriptures. When he learned he was to be arrested if he refused to recant, Luther escaped by night and returned to Wittenburg.

Fortunately, politics were on his side for the moment. As one of the electors of the Holy Roman Emperor, the Pope did not wish to upset Luther's prince, Frederick the Wise. A truce was called in which both the Pope and Luther agreed to abstain from further controversy. Of course, neither would obey the truce for long.

In July of 1519, a professor from Ingolstadt named John Eck challenged one of Luther's colleagues at Wittenburg to an academic debate. The colleague, Karlstadt, was a convert to Luther's way of thinking, and in fact more radical in some ways than Luther himself. (Luther later wryly remarked of his friend: "He has swallowed the Holy Spirit, feathers and all.")

Luther accompanied Karlstadt to the debate, which was held in Leipzig. As Eck had hoped, Luther wound up participating directly. He demonstrated a superior knowledge of the Scriptures, but Eck was highly skilled in the art of debate. Luther was led to state that councils can err, and that the average Christian with the authority of Scripture has more power than a council or the Pope himself. Eck considered himself victorious, for Luther had proved himself to be a heretic just like Hus. From this point forward, anti-Lutheran propaganda often portrayed the monk as "the Saxon Hus."

Excommunication

Luther spent the next year developing his ideas, teaching, and writing. His most important treatises of this period include Address to the German Nobility, On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and Freedom of a Christian.

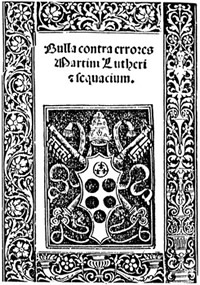

On October 10, 1520, Luther received a papal bull (official proclamation from the Pope). Entitled Exsurge Domine ("Arise, O Lord"), the bull began by dramatically appealing to God to protect his church from the threat of Luther.

Arise, O Lord, and defend Thy cause!

A wild boar has invaded Thy vineyard. Less poetic was the papal bull's sober message that Luther would be excommunicated if he did not recant within 60 days. In Catholic doctrine, in which salvation is only available through the church, excommunication amounts to eternal damnation.

Luther, once a trembling Catholic kissing each of Pilate's steps in Rome, publicly cast the bull into a bonfire. He was officially excommunicated by the Pope on January 3, 1521.

Diet of Worms

Emperor Charles V opened the imperial Diet of Worms (pronounced "DEE-it of Vorms") on 22 January 1521. Luther was summoned to renounce or reaffirm his views and was given an imperial guarantee of safe-conduct to ensure his safe passage. When he appeared before the assembly on 16 April, Johann Eck, an assistant of Archbishop of Trier, acted as spokesman for the Emperor. (Bainton, p. 141) He presented Luther with a table filled with copies of his writings. Eck asked Luther if the books were his and if he still believed what these works taught. Luther requested time to think about his answer. It was granted.

Luther prayed, consulted with friends and mediators and presented himself before the Diet the next day. When the counselor put the same questions to Luther, he said: "They are all mine, but as for the second question, they are not all of one sort." Luther went on to say that some of the works were well received by even his enemies. These he would not reject.

A second class of the books attacked the abuses, lies and desolation of the Christian world. These, Luther believed, could not safely be rejected without encouraging abuses to continue.

The third group contained attacks on individuals. He apologized for the harsh tone of these writings, but did not reject the substance of what he taught in them. If he could be shown from the Scriptures that he was in error, Luther continued, he would reject them. Otherwise, he could not do so safely without encouraging abuse.

Eck, after countering that Luther had no right to teach contrary to the Church through the ages, asked Luther to plainly answer the question: Would Luther reject his books and the errors they contain? Luther replied:

"Unless I am convicted by Scripture and plain reason — I do not accept the authority of popes and councils, for they have contradicted each other — my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe." According to tradition, Luther is then said to have spoken these famous words:

"Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me. Amen." (Bainton, pp. 142-144) Private conferences were held to determine Luther's fate. Before a decision was reached, Luther left Worms. During his return to Wittenberg, he disappeared. The Emperor issued the Edict of Worms on May 25, 1521, declaring Martin Luther an outlaw and a heretic and banning his literature.

The Peasants' War

A Nighttime Kidnapping and Exile in Wartburg

Luther's disappearance after the Diet of Worms was planned. Frederick the Wise arranged for Luther to be seized on his way from the Diet by a company of masked horsemen, who carried him to Wartburg Castle at Eisenach, where he stayed for about a year. He grew a wide flaring beard, took on the garb of a knight, and assumed the pseudonym Jörg (or "Knight George"). During this period of forced sojourn in the world, Luther was still hard at work upon his celebrated translation of the New Testament, though he couldn't rely on the isolation of a monastery.

With Luther's residence in the Wartburg began the constructive period of his career as a reformer; while at the same time the struggle was inaugurated against those who, claiming to proceed from the same Evangelical basis, were deemed by him to swing to the opposite extreme and to hinder, if not prevent, all constructive measures. In his "desert" or "Patmos" (as he called it in his letters) of the Wartburg, moreover, he began his translation of the Bible, of which the New Testament was printed in September 1522. Here, too, besides other pamphlets, he prepared the first portion of his German postilla and his Von der Beichte, in which he denied compulsory confession, although he admitted the wholesomeness of voluntary private confessions.

He also wrote a polemic against Archbishop Albrecht, which forced him to desist from reopening the sale of indulgences; while in his attack on Jacobus Latomus he set forth his views on the relation of grace and the law, as well as on the nature of the grace communicated by Christ. Here he distinguished the objective grace of God to the sinner, who, believing, is justified by God because of the justice of Christ, from the saving grace dwelling within sinful man; while at the same time he emphasized the insufficiency of this "beginning of justification," as well as the persistence of sin after baptism and the sin still inherent in every good work.

Luther's Death and Legacy

Luther's Death and Legacy